|

|

|||

|

|

Home > About Us > News and Articles >Lean Manufacturing

LEAN IN THE JOB SHOP Think “Lean” Doesn’t Apply if You Have Very By David R. Dixon

Talk to typical trailer manufacturers and they will often tell you that lean manufacturing techniques are reserved for those who enjoy a limited number of product variations produced in fairly high quantities. “Lean won’t work for us because we make custom trailers in small quantities.” Or in other words: “We are a ‘job shop’.” A persistent myth pervades the job shop community. It suggests that the strategies and tools that have “leaned out” countless manufacturing operations around the world are simply not applicable in low-volume, high-mix environments. This article, the first in a series, aims to debunk the myth, factually and logically, once and for all. There are, to be sure, certain problems with the application of lean tools in a job shop that we will have to address. We want to offer ideas and suggestions on how to implement lean, and we will ultimately demonstrate to the reader that embracing lean will provide a true competitive advantage and economic benefits that provide a decent return on the investment in the implementation effort. This done, our “lean won’t work in the job shop” myth goes up in smoke, and we can get on with the application of lean’s powerful set of process improvement tools.

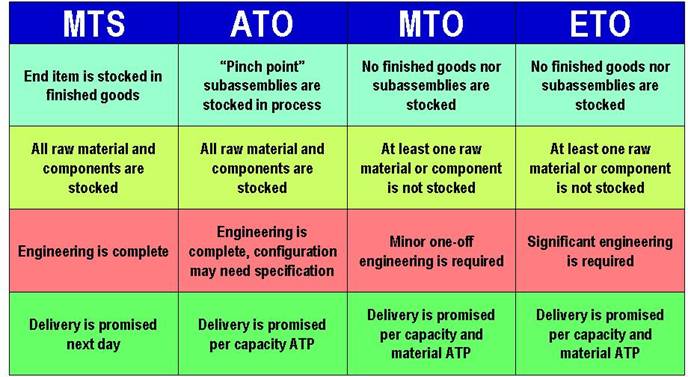

THE PROBLEM The markets we serve drive us to a given manufacturing strategy. Figure 1 illustrates the spectrum of alternatives, from a Make-to-Stock (MTS) approach on one end to an Engineer-to-Order (ETO) environment on the other. Assemble-to-Order (ATO) and Make-to Order (MTO) are “in between” strategies that cater to different customer needs. Most MTS and ATO manufacturers are original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) with marketing and design capabilities. MTO and ETO companies are often (not always) suppliers to OEMs.

And herein lies the definition of a job shop: a company with many customers who buy a wide variety of products in relatively small lot sizes. The degree of repetition is low for any one product, and the aggregate demand is “lumpy.” Failures in customers’ order planning processes create crisis conditions in the job shop, and we measure success by how well we respond to those conditions. Now consider the “granddaddy” of all lean applications, the Toyota Production System. Toyota is clearly an MTS, OEM company—a far cry from the somewhat chaotic MTO/ETO environment of the small job shop. Is it any wonder, then, that shop owners and managers question the applicability of a “Toyota” type system in their world? Add to that the fact that there have been too many failed attempts to force-fit the repetitive lean model in the job shop, and you have the basis for widespread rejection of the whole idea. The myth has evolved from the notion that there is a rigid template for implementing lean. Fortunately, there are some who have used a more flexible approach to achieve tremendous improvements in job-shop performance. JOB-SHOP LEAN Every manufacturer has the same market driven objectives:

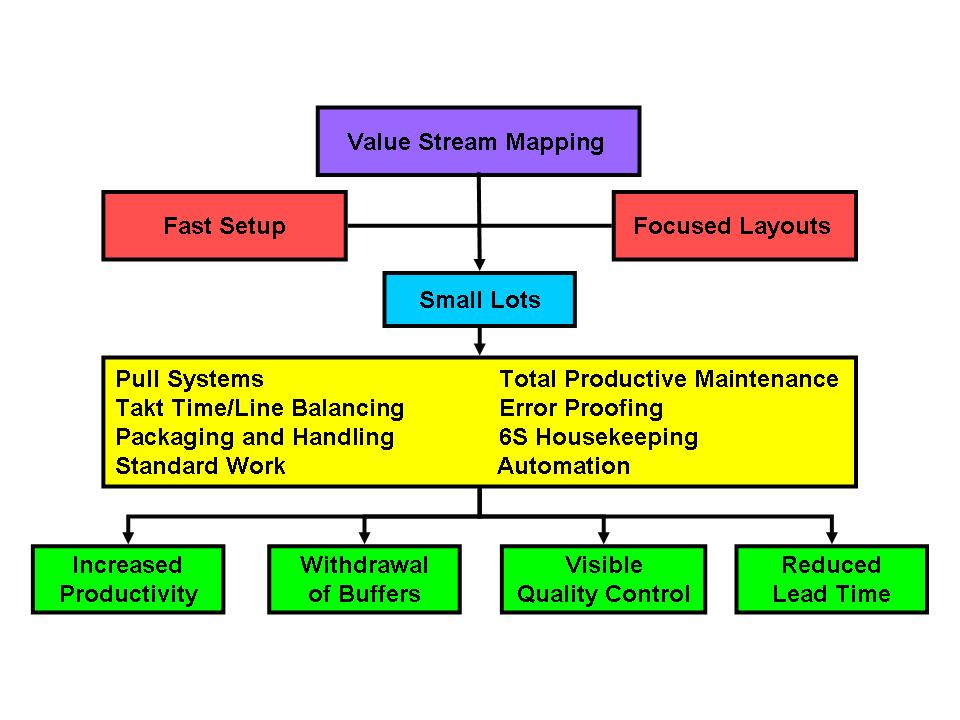

Figure 2 depicts the basic lean tool kit (upper part of the diagram) and the desired outcomes across the bottom. Clearly, these outcomes support directly the common set of objectives listed above.

The trick is to selectively learn and apply the lean tools that help to achieve the objectives in a given shop while de-emphasizing or ignoring those that do not apply. The job Shop Lean Application chart on this page speaks briefly to the purpose of each tool and, in the right hand column, suggests the role of the technique in the job shop. Note that some tools, such as takt time/line balancing, focused layouts and pull systems are adapted to the low volume, high variety shop. And others, such as setup reduction, 5S workplace organization and error proofing are particularly important. Also note the chart’s references to applying lean tools to improving front-end processes. These activities prepare orders for release to the floor, and in many shops every order passes through this process. Delays or errors associated with the front end are passed on to the shop where the cost of correcting problems escalates exponentially. Many shop supervisors would tell you that if we could only fix the problem of late or faulty job packets, the rest would be easy. Thus we have a heavy emphasis on applying lean tools to enable the timely delivery of perfectly “clean” orders to the shop. Order-planning requirements are typical of the many differences between the job shop and the OEM. If orders are repetitive, process documentation is prepared one time, documented as standard work, and fine-tuned over time. In the job shop, the critical standard work is the preparation of process documentation that may only be used one time. It is also difficult to dedicate resources in a small shop, so we may employ virtual cells or the “cell for a day” concept. Sometimes we use mobile equipment to set up temporary cells. A push-pull variation on true demand pull systems is more common in the job shop, and we may measure performance to a run rate of planned labor hours rather than a takt time based on piece-parts. Setup reduction at constraint resources will be pursued relentlessly, and preventive maintenance routines will be highly developed. And, of course, we will use error proofing, both in the front-end processes and in the shop to “get it right the first time.” CONCLUSION There is one underlying objective that we share with higher volume OEMs—we want to enable a flow of work through the shop. Perhaps the OEM flows parts or products one at a time. We may flow small lots or orders, but flow we will. As our selective, appropriate application of lean tools bears fruit, we will become ever more compliant with the Golden Rules of Flow:

There are hundreds of small shops who have discovered the combination of lean tools that have allowed them to flow their work through a waste free process. They are dominating their local markets and putting extraordinary profits to the bottom line. Isn’t it time you did the same?

Contact Us for a Free Assessment!

|

||

|

|